The Anchor in the Emergency Copy

“We shouldn’t use the anchor in this manoeuvre, but we should always keep it ready in case of emergency.”

The pilot always says this phrase before starting a manoeuvre unless the anchor is part of its strategy. The anchor, once unleashed, has a mechanical release mechanism: the brake is released, and the anchor drops. Once the appropriate shackles are paid out, and the brake tightened again, the anchor begins to do its job.

Anchoring is a routine operation onboard, like mooring/unmooring or loading/unloading cargo. But despite being a frequent operation, several incidents related to anchoring occur. Many minor incidents never come to light to a broader audience. Only the insiders are aware of them. Anchoring is not child’s play.

The planning begins days before anchoring and starts with the careful control of the anchorage area to understand if:

- The depth is suitable for the ship we command and complies with the required UKC.

- The nature of the seabed is appropriate and free from wrecks, cables or pipelines, or other obstructions. – Clay gives best-holding power – Shingle and sand have good holding power – Pebbles and cobbles have low holding power – Rocks and sand slopes have poor holding power.

The Master has to:

- Refer to the SMS policy procedures.

- Ensure that the weather forecast for the anchoring period is available for the entire duration.

- The port-specific information is updated: Admiralty Sailing Directions – Pilot Books – “Guide to Port Entry” – large scale charts, and ECDIS.

Pay attention to nautical symbology. One particular symbol that many distracted seafarers ignore is “#“. This symbol indicates foul ground. A safe area for surface navigation but to be avoided by vessels anchoring may have remains of a wreck or a cleared platform.

In planning, the Master must instruct the bow station crew on dropping anchor, whether “Let go” or “Walk back”, which anchor to use, and how many shackles to payout, considering the depth.

Before arrival, the crew will have to carefully inspect the windlass and its hydraulic parts and release the lashings on both to prepare for any order coming from the bridge via the predetermined dedicated VHF channel.

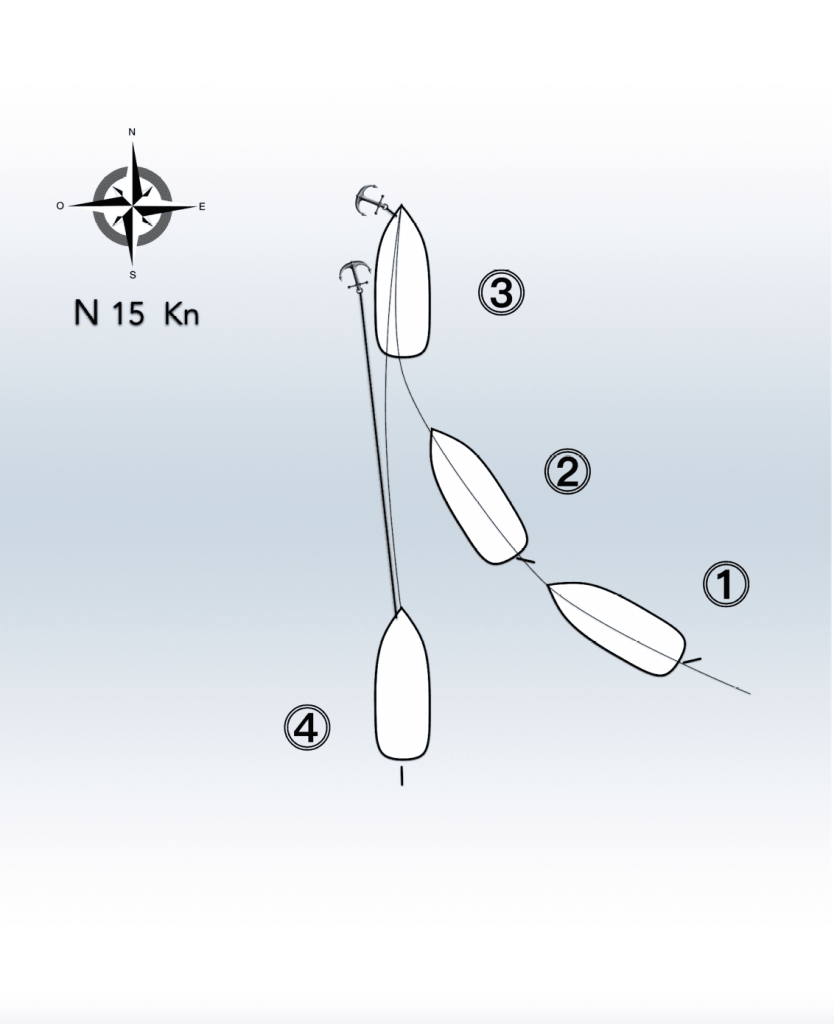

As we have already said, if the sea room, the draft, and the density of the ship traffic allow it, the approach to the anchorage area must take place at minimum speed with a heading into the wind or tidal current. Once on the anchor set point, the ship must proceed astern, and according to the paddle-wheel effect, we must choose the anchor to use. In the case of a right-handed propeller, it will be the port, contrary to the starboard, to avoid the cable crossing the bow during the anchorage procedure.

guidance is issued to Masters

Guidance to ship’s Master issued by The Nautical Institute following an accident during anchoring manoeuvre: 200216 Anchorage Manoeuvring – The Nautical Institute

Once the anchor is “Brought up” and the chain stretch on hold and slacks again in the rest position, the crew must activate the “stopper” to prevent damage to the windlass generated by the vessel’s movement during its stay.

The chain stopper is installed between the windlass and hawse pipe to absorb the chain’s pull by 80% of its breaking strength. The crew must engage the chain stopper during anchorage and passages.

An emergency can occur at any stage of the anchoring operation. It can affect the ship, steering system, engine, hydraulic systems, communication devices, etc. Even minor malfunctioning or mishandled parts can create a ripple effect that leads to an emergency.

For example, the stopper we have just seen can become a problem to be managed in an emergency in case of unexpected bad weather conditions. It can happen that when high waves and rough seas arrive, the stopper can jam or deform. In cases like these, weighing an anchor or letting go in an emergency could be problematic.

Blackout is one of the most feared panic emergencies. When the lights go out on the bridge, and everything shuts down, a sense of impotence rises.

Fortunately, manoeuvring in harbour, the anchor use in an emergency is always possible, even in a blackout. What are the circumstances in which you need to be particularly careful before letting go and holding the anchor?

Speed

It is not so easy if you are onboard a loaded heavy ship, proceeding at high speed and deciding to drop an anchor to stop her. It all depends on the circumstances. On the two sides of the scale, we must put the consequences of a possible impact or collision and the risks or damages for the crew and the windlass system.

The Seabed

There may be so little UKC (under keel clearance) that we risk dropping the anchor, skewering the anchor flukes in the hull.

A Non-free Stretch of Water

We may have a tugboat or mooring boat under the anchor hawsepipe. Submarine electrical pipes/cables: assess whether the severity of the emergency justifies any other damage.

The above points are examples of questions we need to answer before dropping an anchor. A decision to be made quickly because:

An emergency is an unforeseen combination of circumstances or the resulting state that calls for immediate action.

200269 Emergency Anchoring The Nautical Institute

Generally, however, if you can use the anchor in an emergency with a heavy ship and a relatively high speed, the advice is to drop both anchors and not be in a hurry to hold on to the brakes. The more cables we can let go into the water, the more the “elastic” effect of the chains lying on the bottom will help to reduce the strain on the windlass.

We should not forget to use the anchors to modify the trajectory. Not only to slowing/stopping the ship. It can help avoid an unavoidable impact or mitigate its effects.

In the following chapter, we will tell you about a “Manoeuvring Experience”.