Manoeuvres and Meteo: The Eye Wants to be Satisfied Too

Weather forecasts are of interest to everyone, but, for some, the information – as precise as possible – of the evolution of atmospheric phenomena is one of the fundamental ingredients of the short and long-distance strategic plan.

We have talked about naval gigantism and how the intensity of the wind and the sea’s strength affect their ability.

We have seen how the Technical Table, which meets daily to study the forecasts of port movements for the next day, pays particular attention to weather conditions.

Indeed, the wind and the sea dictate the game’s rules.

In the overall view, it is necessary to evaluate:

- number of ships arriving and departing

- port movements

- contemporaneity

- special manoeuvres

Each described situation needs – or not – pilots, tugs and mooring men. Correct programming allows time optimisation, saving money for users, risk containment, and general efficiency.

The “normality” described above can be attacked by various factors, such as:

– management of large ships at the same time;

– particular manoeuvres that require the long-term commitment of nautical and technical services;

– unfavourable weather conditions;

– etc.

In this case, it is necessary to carefully evaluate the weapons available to deal with unforeseen events or worsening conditions.

If a strong wind is expected – based on the available number of tugboats, any shore tension, the berths assigned and the size – the number of ships that can stay simultaneously in a given quay will be planned, the manoeuvres and the intervention strategy.

So far, we are in the ordinary.

Things change when the crystal ball breaks.

It was a quiet summer night, and, with a colleague, we went out in the pilot boat to meet two ships: a 140-meter-long container carrier for him and a small 90-meter Ro-Ro for me.

Flat sea and no wind; both were ships that frequently call our port; friendly captain—non-essential ingredients, contributing to a relaxed atmosphere.

The N. was an “old” ship, equipped with two engines, without thrusters, with low draft and, squeezing the few horses she had; she could barely reach the speed of 8/9 knots.

As I passed the red abeam of the entrance, I heard my colleague on the VHF calling the usual tugboat provided for his manoeuvre.

I was chatting quietly with the captain when I realised that the sea’s surface was no longer reflecting a little further on in the outer port area: a light breeze was drawing alternating streaks of light/dark flickering against the background of the portlights.

Nothing to worry about. A little fresh air flowing from the mountains would only cool us off from the summer heat, at least that’s what I thought until then.

Ten minutes later, I began to worry; I distinctly saw a cloud of coal, illuminated by the light towers present in a quay, moving south: the breeze had turned into the wind and, from what I perceived, it was blowing at least 20 knots.

I called my colleague on the radio to warn him, but the situation was changing quickly even where he was.

Keep in mind that it was not yet an emergency if we can say so, an increase in attention, a manoeuvre that, from being easy, was becoming more and more challenging. I was sure the wind had peaked; it was summer, the forecast was for excellent weather, and it was flat calm until a few minutes before.

We proceeded close to some port obstructions for the next ten minutes; consequently, the wind dropped considerably. Still, the almost horizontal smoke of a chimney far to the West revealed the persistence of a situation that one should never underestimate.

The wind hit us again at the end of the canal-protected part. I had to increase the engines to contain the drift towards the breakwater. We reached a balance with 8 knots of speed and a close-hauled pace.

There was no time to call a tugboat and always counted on the mistaken belief that the wind would not increase any further.

Also, by now, we had almost reached the point of turning.

30 knots.

I was starting to get worried.

At that point, I had two possibilities: not to rotate, put the bow to the wind, drop the anchor and wait for the tug, or continue as planned.

The ship was old and far from being powerful, but she was small – and therefore, I had a fair amount of space -two engines – which would have helped me in rotation – and I had managed to get over the wind in a good way.

I opted for the second solution.

I aimed the bow on the western corner of the first quay, speed 7 knots. I was counting on the shelter of the pierhead to gain a few more meters on the wind.

I order for the engines full astern.

When the speed dropped to 5 knots, I stopped the port engine and shortly after, the direction of the bow shifted, clearing the edge. A minute later, I lost the shelter and the wind, beating on the bow, helped me in the turning until the whole ship came out into the open area because, at that point, a determined leeway began, indeed, very decisive.

I waited for the bow to fall better, and, to help it, I used a kick ahead with the starboard engine and the rudder hard a port.

I had to carry the stern to the wind despite the fear of not having enough power to stop the run towards the breakwater concrete.

Finally, it was time to put the engines full astern.

The ship slowed down, steadily but very slowly.

We stopped a few meters from the obstructions. We stood in a stalemate for a few interminable minutes.

Then, finally, we began to pick up the wind.

It was not easy to get the vessel to the berth because, without thrusters and with small engine power, the wind prevented us from keeping track of the direction, causing us to fall now on one side and now on the other.

It was a manoeuvre that we recalled numerous times with the captain in the following years. Neither of them had ever happened to be amid such a sudden change in the weather.

What do we take home from this experience?

Many things, but today I want to emphasise the importance of picking up the signals.

A careful eye – and that of those who manoeuvre must always be so in a particular way – must be able to grasp the signals arriving from the environment in which it operates.

The anemometer indicates the wind strength and direction at that moment and in that precise position.

The situation a few hundred meters ahead could be completely different.

Let’s try to make a list of how we may obtain the information that interests us:

- In the first place, we have an accurate weather forecast; there are many possibilities to clear your mind, finding what is of interest from the numerous sites available and, for more in-depth needs, there are consolidated companies with great experience and reliability such for example, navimeteo.com, which provide highly personalised data depending on requirements;

- Second place is the weather stations in the area of interest: those managed by the System Authorities, those in the terminals, in the various airports, and up to the anemometers fitted to the quay cranes. A good indication of the wind situation is usually by looking carefully;

- Third place, but no less critical, are the natural indicators. A glance at the ships at anchor can make us understand if we are in current presence and if it wins over the wind. Smoke, of any kind, gives us a reasonably precise indication of wind intensity and direction. The sea’s surface, flat, barely marked, streaked with white, and the presence of “sheep” or even wave motion within sheltered waters are clear signals.

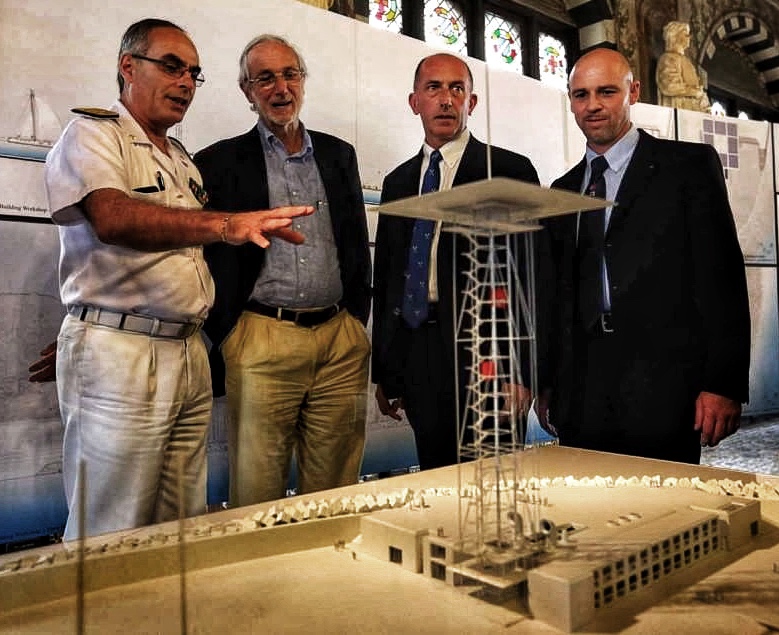

The new “Torre Piloti” design, coming from the pencil of the architect Renzo Piano – a person with incredible human and professional qualities – includes a long and thin pole resembling an antenna on its top. Its bending movements will instantly indicate the strength and intensity of the wind to ships entering the port.

Let us remember that the general orography changes the situation radically, even at a distance of a few tens of meters. For this reason, it is important to have as many indicators as possible and, above all, never underestimate them.